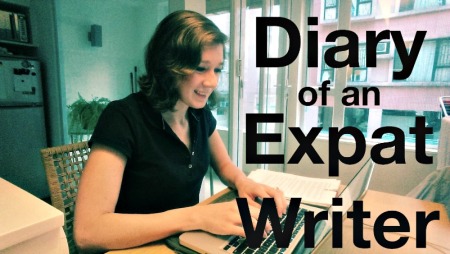

Columnist Doreen Brett is back, and she’s accompanied by another “great” in the expat publishing world, Jo Parfitt, who has published 30+ books herself while also helping at least a hundred new expat writers publish their first great works. Wow. Who among us can compete? —ML Awanohara

Hello Displaced Nationers! It is my pleasure to present to you the venerable Jo Parfitt, who has been an expat for more than three decades while also carving out a career for herself as author, journalist, writing mentor/teacher, and publisher.

This is not Jo’s first time on the Displaced Nation. A couple of years ago, another expat author, Ana McGinley, interviewed Jo about her decision to found Summertime Publishing, which specializes in publishing books by and for people living abroad.

Summertime, by the way, is turning 10 years old this year. Congratulations, Jo!

As Jo reported to Ana, one of her own books, A Career in Your Suitcase, remains one of Summertime’s top five bestsellers. Is it any wonder, given that Jo is her own best example? Among the many places where she’s lived and worked are three I know well: my native Malaysia, my husband’s home country of Britain, and my current home of the Netherlands, where Jo, too, now resides.

And now let’s hear about Jo’s experience as a serial expat—and how living in so many different places has fed her creative life.

* * *

Welcome, Jo, to the Displaced Nation. First let’s do a quick review of all the places you’ve called “home”. You were born in Stamford, a town in Lincolnshire, UK. A few years back, Stamford was rated the best place to live by the Sunday Times. But you were not content to stay put. Instead you have lived in Dubai, Oman, Norway, Kuala Lumpur, Brunei, and the Netherlands. What got you started on this peripatetic life?

I went abroad the day after I got married, when I was 26. My boyfriend had gone to Dubai for work and I had to marry him to follow him. Before that happened, I already knew I loved being overseas. I had done a French degree and a year abroad, so I was already travelling before I met my husband. But still, I hadn’t imagined living in Dubai and, in fact, did not want to go there at all. But my husband (he was my fiancé at the time) said: “Come for six months. If you don’t, you’ll regret it for the rest of your life.” And thirty years later, we are still living abroad…

Why didn’t you want to go to Dubai?

At that time I was running my own business and doing quite well. And I was really happy in my career and didn’t want to give it up. Career has always been really important to me. When I closed down my business (I was in a partnership) to move to Dubai, I found it absolutely devastating.

So Dubai was a hard landing?

I was the first expat wife in my husband’s company. They had no support for me at all. We weren’t given our own apartment. I ended up sharing a flat with some other chaps who were in my husband’s office. I was lost and lonely and I knew nothing about networking, I knew nothing about portable careers, I knew nothing about being an expat. But then I found a job opportunity for somebody to do some freelance CV writing. So I did, and eventually I became a journalist. When I submitted my CV they said: “Well you’re not very good but you’ve got potential. So you work for me and I’ll shout at you a lot and you’ll learn.” So that’s what happened. One thing led to another and I had a career again.

Can you tell us about where you went next?

From Dubai, we went to Oman for two-and-a-half years, which was heaven. We loved it. We left too soon because after Oman we went to Stavanger, in southwestern Norway. We went from heat and and living outdoors and having help in the house to a cold and rainy place with no help. We stayed 18 months—actually, we cut that posting short. (I’ve been back to Stavanger since and I thought it was wonderful, but at that time, it was just not for me.) We moved back to Stamford, but I didn’t fit in anymore. We were based in the UK for seven years while my husband would commute on the plane or bus or train for work, until finally we decided it was time we all stayed together as a family again, and we went to live in The Hague. My husband and I also moved to Brunei for a short posting, staying just a few months before returning to The Hague. From there my husband got a job in Kuala Lumpur. For me, living in Malaysia was a dream come true. We’d traveled to Southeast Asia while living in Dubai, and I knew right away I wanted to live in that part of the world some day. It was fantastic.

When you repeat being an expat so many times, do you end up being drawn to cities, where you’ll find other well-traveled people?

In Dubai and Oman it was impossible to get to meet the locals; one has no choice but to live in the expat bubble. In Norway, my home was on the edges of the expat bubble because I didn’t feel that they were really my kind of person. To be honest, I don’t know who I thought my kind of person was. I was depressed in Norway, so nothing would have made me happy. When I went back in England, I realized I didn’t fit in anymore because I’ve lived overseas, so I found my community by starting up a professional network of women writers.

In general have you found that living in cities tends to feed your creative drive?

I wrote a blog called Sunny Interval while based in Kuala Lumpur. I wrote briefly in Brunei. Wherever I went, I found things to write about, generally about transition. I am a poet and a columnist at heart. I love finding parallels and being able to compare and contrast cultures. That said, I lost my mojo in KL for quite a long time—I couldn’t seem to find the beautiful bits. But then I had an experience that absolutely changed my life: an opportunity to write a book on Penang, which is located on Malaysia’s northwest coast. As part of the research, I had to interview Penangites, I had to understand the history and get under the skin of the place. That’s when I realised that getting under the skin of a place is the thing that WILL feed your soul, even if the place is not inherently beautiful. It was such a privilege to get to know Muslims and Buddhists, Chinese, Malay, and Indian, and call them all friends.

Does language tend to be a barrier when you’re in a non-English speaking place?

Even though I’m a linguist, I didn’t learn Arabic or Norwegian, I know very little Dutch. But when I went to Malaysia, I decided that I would learn Malay, and it made a huge difference. Boleh lah! (Can do!) And now that I’m back in The Hague, I’m determined to speak more Dutch. I think it’s very important to learn the language, and I am ashamed that I didn’t learn Arabic or Norwegian, or Dutch the first time around.

How about the more remote places you have lived? Do they, too, feed your creativity and if so in what ways? And how do you keep from feeling isolated?

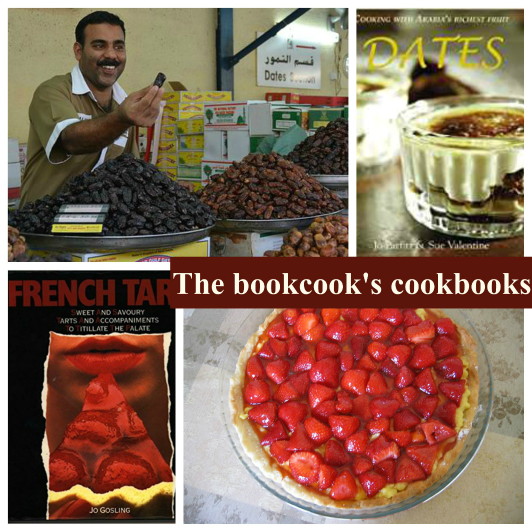

I write! As I mentioned, I did a degree in French. As part of my studies, I did a year teaching in France in a really boring small town and I didn’t have any friends there either. I would walk around the town for something to do. And I would walk in the shops and I would look in the windows. And I looked at the wonderful display of tarts and I just thought: “”French Tarts”—that’s a great title for a book. I’ll write it.” And what it did was it gave me something interesting to do and a way to meet people and eat (which I loved!). Because I couldn’t cook I decided to ask everybody I met in the town if they’d have me to dinner, and if they had me to dinner they had to make me a tart and I would write about it and would put their recipe in my book! I was 20. I had utmost confidence that they would say yes. So I went to dinner with the doctor, the dentist, the lady who ran the baby shop, teachers from the school, the man who ran the bicycle shop… I just said to anybody, I want to come to dinner. And I wrote the draft of French Tarts, which came out when I was 24. That was my first book.

What a great story! And I happen to know that’s not your only cookery book. After all, you brand yourself as a bookcook…

When I was in Oman, I had the idea with a friend of mine of writing a cookbook on dates because none of the expats knew how to cook with dates. So we wrote a cookbook on dates. We invented the recipes (I could cook by then!) and did everything else. Though it looked terrible, it sold very well because people wanted the content.

Are there any other remote places where you’ve lived that have fed your creativity?

The most remote place I’ve lived in was Kuala Belait in Brunei, which for those who don’t know if a small sovereign state on the north coast of the island of Borneo (the rest of the island is Malaysian and Indonesian). Kuala Belait was really remote. There was nothing to do there at all. I actually went online and googled bloggers in the area. And I found one blogger, who was 20 years younger. I met her for coffee. I did everything I could to find people. In the end, I started a writer’s circle. I ran a few writing classes and joined a French conversation group. And I was only there for three months. You have to make an effort to reach out to people, but the Internet does make it easier.

I know you’re a great networker. Do you tend to network online or in person?

I network with people online. But I also make sure I network with people in person. I sometimes think, it’s been three weeks and I haven’t seen anybody apart from my family, so I get on the phone and book lunches and things.

Do writers sometimes find it a struggle to meet people IRL?

When I was working from home as a writer, I realised that if I stayed in all day and all evening and wrote, I got depressed. And so I used to go for a walk at lunchtimes and at least try to engage with somebody in a shop. I am an introvert when I work. But I feed my soul by being out. I like to see people face to face every week. I don’t think you get much energy from talking to somebody through the email and texting.

You have 31 books! Do you have a favorite?

Out of my 31 books, I would say that a couple have been pivotal for me. One I’ve already mentioned: French Tarts. It made me realise that If you’ve got a good idea, then you can do anything. The other is A Career in Your Suitcase, which is now in its fourth edition and still going strong. I had the idea for writing it when we first went to Norway. There were no English publications for me to write for. I started working on this and an expat anthology called Forced to Fly.

What’s next for you, travel-wise and creativity-wise: will you stay put where you are or are other cities/artistic activities on your horizon?

I’m in The Hague now. I like belonging in a community. I love the fact that everything’s familiar. When you’ve moved and moved and moved, you really want to feel that you belong somewhere. And knowing the way and not having to use a map and knowing where the doctors is: it’s a great feeling. Here in The Hague I’ve also come back to old friends, and that’s been fantastic. I didn’t have friends in England really. They’d all gone off to university or wherever. England was difficult. I think Norway was the hardest. England was the next hardest. Coming back here to the Netherlands has been the easiest because it wasn’t a repatriation as I thought it might feel. It was a reposting. It had all of the positives and none of the negatives.

Tell me about your new venture taking writers away on retreats. I believe you call them “me”-treats?

This has been an ambition of mine for some time. I’m holding what I call Writing Me-Treats. These are residential holidays for four or five nights. They’re for people who love to write, to come and indulge in writing and sharing and doing beautiful things that will make them feel really inspired. For example, in The Hague, we will do the walk in the Jewish quarter and talk about what happened to the Jews. Understanding that has really deepened my love of the place. My first writer’s Me-Treat is in Penang, this month. My next writer’s Me-Treat is in The Hague, which I have timed to be exactly after the Families in Global Transition (FIGT) conference. The next one is in France, in a mini chateau. Then Devon. Then Tuscany.

Do you have any advice for other global creatives?

If you’re a writer, try getting into a writers circle. That’s where I found my soulmates. People come, we do some speed writing, we share what we’ve written, then I create a task and we do an exercise. It’s about being forced to write, not having an excuse or procrastinating. It shows people what they can do in 10 minutes. It empowers them to think they are good enough. I think a lot of writers want to keep what they’ve written to themselves because they’re too afraid to share it. Or they’re too scared that somebody else will plagiarise it. Which is a real worry. What you get in a writer’s circle is a safe space. People get very friendly. They get very close.

I should remind our readers at this juncture that you have your own publishing house for expat books.

Yes, I run Summertime Publishing. I’ve been helping people to write books since 2002. I teach people online and have three online courses: people can study by email as well. Four years ago I decided to run this writer’s scholarship, the Parfitt-Pascoe Writing Residency. I would train writers, they would cover the FIGT conference, and I would publish what they wrote. This is about to be my fifth year. It’s a wonderful opportunity for people to get training from me for free, to get lots of mentoring for free, and to increase their network.

Any recommendations for the wannabe writers out there?

The other thing I would recommend is that you either write a journal, and do it religiously, or write a blog. Whenever something happens, that I think is of note. I write a blog post. I write it for people I know, so I feel safe enough to be authentic and vulnerable, to show how stupid I am, and my mistakes. And I write as if no stranger will read it. And it becomes a record of my life. A lot of people are very scared to expose themselves like that. But don’t be.

Thanks so much, Jo, for sharing your story with us.

* * *

Readers, any further questions for the extraordinary Jo Parfitt on her thoughts about place, displacement, and the connection between the communities you’ve lived in and creativity? Any authors or other international creatives you’d like to see Doreen interview in future posts? Please leave your suggestions in the comments.

STAY TUNED for this coming week’s fab posts.

If you enjoyed this post, we invite you to register for The Displaced Dispatch, a biweekly round up of posts from The Displaced Nation—and so much more! Register for The Displaced Dispatch by clicking here!

Related posts:

Photo credits:

Photos via Pixabay.