Tracey Warr is here with Dianne Ascroft, a Canadian writer who left the hustle-bustle of Toronto for Northern Ireland, a place she found so compelling that she ultimately settled in the countryside and has specialized in writing books set in that part of the world.

Greetings, Displaced Nationers. I hope your summer is off to a productive start. To give you that extra inspiration, I hope you’ll enjoy my interview with this month’s writer, Dianne Ascroft.

Dianne grew up an urban Canadian, in Toronto. But those roots would hardly be apparent if you met her now. In the 1990s she moved across the water to Northern Ireland, where she still finds herself a quarter-of-a-century later.

Dianne started out in Belfast, where she moved for work. Then, after living in Troon, a town on the west coast of Scotland, for a spell, she returned to Northern Ireland and settled into rural life in County Fermanagh, with her husband and their assortment of strong-willed animals.

Dianne says that this gradual downsizing of her surroundings reflects her pursuit of a writing career. Since moving to Britain, she worked in various offices and shops; but her head was always in books and she harbored a passion for writing. She is an avid reader and started writing her spare time more than a decade ago. Now that she is living in the countryside, she can concentrate on writing fulltime.

“When I’m not writing,” she says on her author site, “I enjoy walks in the country, evenings in front of our open fireplace and folk and traditional music.” She also plays the Scottish bagpipes though has given this hobby up since moving to the farm, which she says is “just as well as it’s rather disconcerting to turn around when you are practicing in a field and find that you have a herd of cows for an audience.”

Dianne mostly writes fiction, both historical and contemporary, often with an Irish connection. “I love where I live and I am fascinated by it,” she says. Her current project is The Yankee Years, a collection of short reads and novels set in World War II Northern Ireland. “After the Allied troops arrived in this outlying part of Great Britain, life here would never be the same again,” Dianne says. “The series strives to bring those heady, fleeting years to life again, in thrilling and romantic tales of the era.”

Her other fictional writings include:

- An Unbidden Visitor, a ghost tale inspired by the famous Northern Irish legend of the Coonian ghost. (Dianne lives a couple of miles from the house that sparked the legend.)

- Dancing Shadows, Tramping Hooves, a collection of six short stories about farm life in Northern Ireland.

- Hitler and Mars Bars, an historical novel about a German boy growing up alone in postwar Ireland.

Dianne occasionally writes non-fiction for Canadian and Irish newspapers. In 2013 she released two e-book collections of her articles: Fermanagh Gems and Irish Sanctuaries.

* * *

Welcome, Dianne, to Location, Locution. Which comes first when you get an idea for a new book: story or location?

The two are very closely related in my writing so it’s rather hard to say. I tell stories that are sparked by interesting items that have caught my attention. Since I write historical fiction mainly, sometimes that’s something I read in an old newspaper or a history text, or maybe something I’ve noticed in the landscape around me. But, no matter what the original inspiration was, my stories will always be inherently part of the place where they are set. They can’t be separated from their location. The Yankee Years, my Second World War series, is set in County Fermanagh where I’ve lived for more than a decade now. The war was a pivotal point in Northern Ireland’s history; and the influx of Allied troops had a major impact on the economy and culture of County Fermanagh. Army camps and Air Force flying-boat bases sprang up, and the population of the county grew until approximately a quarter of the entire population consisted of military personnel. Fermanagh must have been so different from the quiet rural area that I know today, and imagining this recent past really intrigued me. The events during the war and their impact on the county grabbed my imagination—and that’s how the series was born.

How is it possible to conjure up the past now that the Yankees have gone home, so to speak?

Despite the impact the war had on Fermanagh, there was an interesting dichotomy in the county. The old way of life was disrupted and challenged by the incomers from unfamiliar cultures; but, at the same time, fundamental aspects of rural life didn’t change so I can easily imagine what farm life was like at that time as small farms are still very much the same today. The continuity of this way of life through the generations is another feature of the province that fascinates me and it is a great bonus for an historical fiction writer. It makes imagining the past much easier to do.

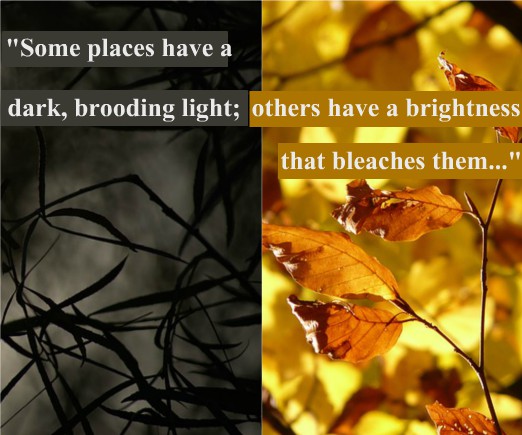

What’s your technique for evoking the atmosphere of a place?

I have to admit that I like lots of detail. I want to paint a picture of the place so that readers feel like they are there. But, I try not to be too wordy, and I follow the guideline that, if readers are likely to be familiar with a place or historical detail, then I don’t need to describe it in great depth. But, if I’m describing a place or item that won’t be familiar to most readers, then I try to show exactly what it was like. By evoking sounds and smells, as well as visual details, I hope to bring it to life in readers’ minds. I think it’s important to draw readers’ attention to details that they may not be familiar with and to use all the senses so they can fully experience it.

But is there any particular feature that creates a sense of location? Landscape, culture, food?

I’d say that all three are important but, for the stories I tell, the landscape and culture are central. The way of life in this rather remote, rural part of Northern Ireland has evolved from the work of the people inhabiting it: making a living from the land or water, farming or fishing. People lived their lives close to the natural world and, therefore, the landscape and culture were intertwined. The people who lived here a couple of generations ago, in the days before mechanised farming, were proud and capable yet they also needed the co-operation and support of their community. My plots are often built around elements of this simple, hardy way of life.

In the case of Northern Ireland, you also have the clash of religions. Do you weave this thread into your stories as well?

When I first arrived, I hesitated to tackle writing about Northern Ireland because of the history of sectarian conflict between Protestants and Catholics that has divided the country into two communities for centuries. This history makes Ireland very different from the society I grew up in, but I think it has to be woven into any writing about this part of the world as it is a unique characteristic of the country. It can be difficult to capture the nuances of life in this complex society where the tensions between the communities stretch back generations and still influence many aspects of modern day life. But, since I wanted to write stories about the Second World War era in Ulster Province, I decided I would have to tackle the issue. I think that viewing the society as an outsider gives me unique insights into it which I can use to convincingly convey the place and the people to my readers.

Can you give a brief example of your latest work that illustrates place?

Here is the beginning of Scene 2 in Keeping Her Pledge, the third story in The Yankee Years Books 1-3:

“Standing at the upstairs hall window in the early evening, her wet hair resting on the towel she had thrown across her shoulders, Pearl looked across the single field that separated the farmhouse from Lough Erne. She watched as a large lumbering Sunderland seaplane sliced through the water, gathering speed until it launched itself into the air. As it lifted off, a torrent of water sprayed out from it and she heard the roar of its engines.

Chuck had said that he wasn’t supposed to tell her but he was on an anti-submarine patrol today. He would have left the base at RAF Castle Archdale, on the opposite side of the lough, soon after first light this morning. There were patrols around the clock, and planes were taking off and landing day and night. She often heard the roars of their engines as she lay in bed, before she fell asleep and as she awoke. Sometimes she would stand at her bedroom window and gaze out at the row of navigation lights that guided the planes in to land, strung out like lanterns on a rope across the field and into the lough.

“I thought you’d be getting ready.” Davy walked up behind her.

“In a wee minute. Isn’t it a lovely night? I was just watching the planes.”

“Looking for your sweetheart, are you?”

“Don’t be daft. And he’s not my sweetheart.” Pearl smiled to herself. Although she had only recently met Chuck, neither of them was seeing anyone else. They were as good as walking out together. No doubt, she would soon be able to tell the world that he was her sweetheart.

“Well, if you’re standing here daydreaming, I’ll wash and shave. Race you to the mirror.”

Davy walked down the hall to the bedroom he shared with their two younger brothers, Charlie and Ian. Pearl hugged herself and sighed as she turned back to the window. The flying boats looked so graceful gliding through the sky, not at all cumbersome as they were in the water. Chuck had told her about the view up there. He said everything on the ground below looked tiny. It was like looking at a miniature picture with new images constantly spinning past inside the frame. She would love to see her house and Lough Erne from the sky. It was such a perfect evening. Chuck just had to return in time to meet her at the dance. She squeezed her eyes shut and wished.

Half an hour later Pearl stood in front of the large walnut mirror in the downstairs hallway. As she ran the brush through her hair, teasing and shaking the tangles out of it, she heard the drone of an aircraft approaching. With RAF Castle Archdale so close, she had become accustomed to the hum of the steady stream of aircraft flying overhead.

She twisted the brush sharply and tugged at a knot as Davy sidled up beside her. Without pausing, she stepped sideways to share the mirror. From this angle, she saw the landscape outside reflected in the glass: peaceful rolling hills divided by rough stone walls and thick hedges. A dark shadow moving rapidly in the top corner of the glass drew her attention. She turned away from the mirror to look through the small window in the front door. The flying boat she had heard was approaching the lough much closer to the ground than they usually flew at this distance from the water.

Davy followed her gaze. When he spotted the aircraft he ran to the door. “That plane won’t make the lough,” he shouted as he jerked the door open and rushed outside.

Pearl followed him. As she stepped outside the door, she heard a high-pitched whine before the seaplane’s engines cut out. The aircraft plunged steeply towards the ground and crashed in the field beside the water. Flames shot up from the wreckage and crackled like a huge bonfire. Davy, her father and two neighbours who had called in for a chat, Tommy Boyd and Dick Morton, were already running toward the aircraft.

Pearl hurried across their farmyard and crossed the road but stopped at the gate to the field. The smoke billowing from the plane nearly choked her. Her stomach clenched as she gawked at the debris strewn across the charred grass and she had to grip the top rail of the gate to keep her knees from buckling. Something gleamed dully under the hedge beside where the aircraft lay. She squinted through the smoke at the seaplane’s massive engine lying there intact and focused on its unsullied bulk, unwilling to look at the carnage surrounding it.”

Thank you for sharing that passage. How well do you feel you need to know a place before using it as a setting?

Because my stories are set in a region that features in few books, fiction or non-fiction, and one which many readers will not be familiar with but I want them to understand, I feel compelled to create for them an almost three-dimensional mental image of it. My first novel, Hitler and Mars Bars, takes place in several locations in the Republic of Ireland as well as the Ruhr region of Germany. During my research for the book, I visited each of the locations in Ireland to see exactly where the story would unfold. I noted minute details about each place so that I could use the relevant ones in the novel. I wasn’t able to travel to Germany but I did study detailed maps and historic photographs of the area where that portion of the story is set so I could imagine it fully as I wrote. The Yankee Years, the series I’m currently working on, is set in various locations in County Fermanagh, Northern Ireland. As for my first novel, I visited each location I had chosen for these stories in order to get a feel for the place. I wanted to be able to see the place in my mind as I wrote. I then also referred to historical photographs of the area to see what it was like during the Second World War when my stories are set. Before I started writing, I compiled detailed information about the physical and man-made landmarks in the region, the distances between various places, the sights, sounds and smells in the region and I drew on all of this information to create real places for the reader to step into.

Last but not least, which writers do you admire for the way they use location?

There are two in particular that immediately spring to my mind, and I have to admit that I admire these writers for many aspects of their writing styles, not only their use of location. What I like best is that they both use lots of detail—to describe characters, settings and the action unfolding in the story. Diana Gabaldon and Manda (M.C.) Scott are the writers I’m referring to. Although I admire both of them, Manda Scott has the edge. There is just something wonderful about her novels. Her ability to breathe life into characters, unveil complex stories and create vivid settings, as well as her skilful use of language, is absolutely wonderful and keeps me enthralled. I love stories like hers, that come alive in my mind.

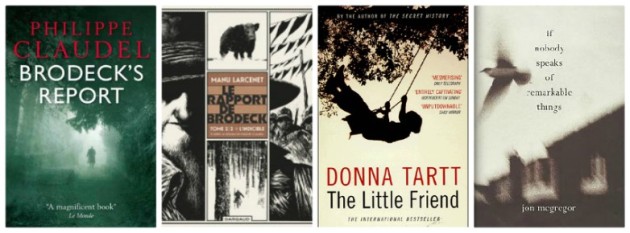

Dianne’s picks for novelists who have mastered the art of writing about place

Thanks so much, Dianne, for your answers. It’s been a pleasure.

* * *

Readers, any questions for Dianne? Please leave them in the comments below.

Meanwhile, if you would like to discover more about Dianne Ascroft and her creative output, I suggest you visit her author site & blog, where you can sign up for her newsletter. You can also follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

À bientôt! Till next time…

* * *

Thank you so much, Tracey and Dianne! I for one certainly wouldn’t expect to meet a Canadian playing the bagpipes in the Irish countryside. Dianne, you are fantastically displaced! As far as your creative output goes, I’m particularly impressed by your “Yankee Years” series. Like many other Americans, I had no idea that the first U.S. soldiers to enter the Second World War landed in Northern Ireland. Good on you for writing fictional histories about that period, which might otherwise be lost to posterity or else overshadowed by all the stories of sectarian violence in that part of the world, AKA The Troubles. —ML Awanohara

Tracey Warr is an English writer living mostly in France. She has published three early medieval novels with Impress Books: Conquest: Daughter of the Last King (2016), The Viking Hostage (2014), and Almodis the Peaceweaver (2011), as well as a future fiction novella, Meanda (2016), set on a watery exoplanet, as well as non-fiction books and essays on contemporary art. She teaches on creative writing courses in France with A Chapter Away.

STAY TUNED for next week’s fab posts!

If you enjoyed this post, we invite you to register for The Displaced Dispatch, a round up of biweekly posts from The Displaced Nation and much, much more. Register for The Displaced Dispatch by clicking here!

Related posts:

Photo credits:

Top visual: The World Book (1920), by Eric Fischer via Flickr (CC BY 2.0); “Writing? Yeah.” by Caleb Roenigk via Flickr (CC BY 2.0); author photo and photos of Irish countryside, supplied; other photos via Pixabay.