Born in: Sarajevo, Bosnia (at the time of my birth, still Yugoslavia)

Born in: Sarajevo, Bosnia (at the time of my birth, still Yugoslavia)

Passports: Happily, I carry a USA passport — and realize how lucky I am!

Cities/States/Countries lived in: Utah (Salt Lake City): 1985-90; Ohio (Columbus): 1991-99; Washington, DC: 2000-01; Washington (Randle*): 2002; Connecticut (Storrs & Hartford): 2003-05 & 2006-08; Germany (Hamburg): 2006; New York (New York): 2008-10, 2011-present; Uganda (Kalisizo Town, Rakai District): 2010-11.

Cyberspace coordinates: Still a work in progress, but stay tuned!

* A small community deep in the temperate rainforest of the Pacific Northwest, between Mt. St. Helen’s and Mt. Rainier.

What made you leave your homeland in the first place?

My mother was accepted to graduate school at the University of Utah. Both my mother and father yearned to leave Bosnia (formerly part of Yugoslavia), for no unusual reasons: they sought greater academic and career opportunities and a better future for their children. They also sensed the progressing demise of our country, which started promptly after Tito’s death. Unlike the rest of our family, friends, and neighbors, my family fled the country before the civil war and genocide began in the early 1990s.

Is anyone else in your immediate family “displaced”?

My parents are definitely displaced. Similar to other immigrants who’ve spent their childhood, adolescence, and young adult years in their home country and then lived more than thirty years in their adopted country, my parents have never quite fit into the United States. The extent to which immigrants like them do or do not have control over “fitting in” remains a mystery to me — resting as it does on so many social, racial, cultural, religious, economic, geographic, and ethnic variables. Maybe they are destined to always feel displaced? People like my parents tend to feel at “home” only when they have found pockets of people from their homeland who have created sub-communities in whatever locales they reside. But then when my parents actually do go home after spending so much time abroad, their friends and family regard them differently: “You’re an American now.” Comments like those — from your own family — can make you feel as though you’re living on the “moon.” You’re seen as something of a traitor, regardless of the amount of remittances you’ve sent home.

Describe the moment when you felt most displaced.

For me, feeling displaced has to do with suffering through a bad life decision — you only realize it’s a terrible choice when it’s too late. Call it poor planning or a penchant for ignoring sage advice, but unfortunately, I have a lot of experience in this realm. Working in Hamburg, Germany, was like that for me. I went there to teach English as a foreign language to Germans. I absolutely loathed the work — and also didn’t have a positive attitude. In retrospect, it’s pretty distressing to think that my time in Hamburg could have been much richer. Although it’s ethnically homogenous and the German culture is a tough one to crack, Hamburg is a wonderful northern European city with an abundance of parks, museums, delicious restaurants, festivals, free events, concerts, shopping, affordable living, social services, and whatever you wish for in a metropolis with enough space to never feel stifled. Yet I felt displaced the entire time I was there.

Describe the moment when you felt least displaced.

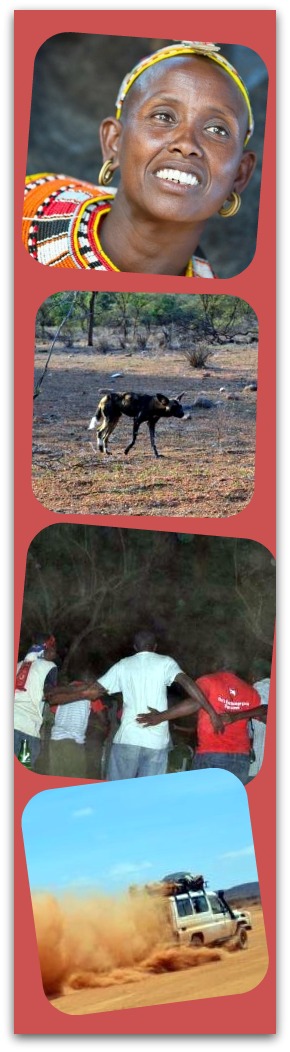

The moment I set foot in the Pearl of Africa. There’s something about Uganda. It’s a loving country — the people are warm, welcoming, celebratory — and the terrain itself, not to mention the climate, is extraordinarily beautiful. All of these elements combined — the beauty of the people, the country, the climate — made me feel instantly at home. Of course, in a place like Uganda, I stick out in the crowd — hence am always at the mercy of onlookers and of people incessantly yelling “Muzungu!” But even when I was the only muzungu for miles and miles, and didn’t understand the language, I felt more comfortable and at peace there, than I have anywhere in the world.

If I had to analyze it, I’d say my comfort level also had to do with the work I was doing in that country. I was on a small team that was part of the Suubi Research Project: we’d been given the task of designing a sustainable school-lunch program for 10 primary schools in southern Uganda. The majority of pupils don’t eat anything all day because their parents/caregivers cannot afford the nominal lunch fees. For those who can afford it, the midday meal consists of boiled maize-meal and water in a soupy consistency. Together with school teachers and administrators, pupils, and community members, we tried to come up with a program that would be nutritional but also generate a profit for schools in the long run.

To do this kind of work, I had to access parts of my brain, psyche, and heart that, in many highly-industrialized Western countries, are frequently subdued, or even sabotaged.

You may bring one curiosity you’ve collected from each of your adopted countries into the Displaced Nation. What’s in your suitcase?

From Zagreb, Croatia: A licitarka srce, an ornamental-sized heart-shaped cookie. Not intended for eating, it’s hardened, painted red, and adorned with loving phrases or sketches of historical sites in Zagreb. It’s a typical souvenir, but hasn’t lost its significance for me. And better yet, it’s small and lightweight.

From Sarajevo, Bosnia: A džezva, a pot used to make Turkish coffee, which locals consume about 4-5 times per day in the street cafes of Sarajevo. Pack it in your suitcase, and its uncomplicated design makes it possible to enjoy a strong Turkish coffee anywhere in the world — as long as there are finely ground coffee beans, water, and fire.

From Uganda: Handmade baskets woven from grasses, tree-bark hats, banana-fiber mats, and colorfully printed smocks. I would give all of these items away as gifts to Displaced Nation residents as I know I’ll keep returning to Uganda.

From the US: All of my iLife appendages — nothing else matters. But if there is still space, I’d pack a good pair of American blue jeans, running shoes, powdered electrolyte drink mixes, and probiotics.

You’re invited to prepare one meal based on your travels for other Displaced Nation members. What’s on the menu?

I’m going to choose the food from my home country, and various other parts of former Yugoslavia, which remains my favorite. I would prepare an assortment of meat, cheese and cabbage burek, with kajmak and kupus salata on the side.

For anyone needing to top off the meal with something sweet, I’d offer plates of oblande, tulumbe, kadaif, and krempite.

Beverages would include red wine from Macedonia and some sort of rakija (domestic spirits) as an aperitif.

And for an African touch, I’d consider including fresh tilapia from Lake Victoria, as well as fresh pineapples, avocado, mango, and papaya.

You may add one word or expression from the countries you’ve lived in to The Displaced Nation argot. What will you loan us?

From Uganda: You are lost. The first time a Ugandan said this to me (they say it in English), it took me some time to realize that in fact, I was very much found. After hearing it time and again, I interpreted it to mean: “I haven’t seen you in a while, where have you been?” or “I miss you.”

From American English: It’s not so much a word but the habit Americans have of inventing new words by converting nouns into verbs or combining two words/concepts: eg, voluntouring, voluntourism, professionalize, beveraging, tween…

This month we are looking into “philanthropic displacement” — when people travel or become expats on behalf of helping others less fortunate than themselves. Do you have a role model you look up to when engaged in this kind of travel — whose words of advice you remember when you find yourself in a difficult situation?

I would choose my father for this one. Some advice he has dished over the years has actually stuck. Many immigrant parents wish their displaced and nomadic offspring would settle down in the burbs already — but not my dad. He genuinely supports what I do. Here’s what he said:

Who you are, in terms of your skin color, gender, ethnicity, ability, whatever it may be, it’s all by chance. No one should be so attached to their position in society, because it could change at any moment, and you didn’t have a choice in the first place.

My interpretation of that is, regardless of how you position yourself or where other people place you in the ruthless global hierarchy, what you value in yourself, in other people, and in life, is of prime importance. You are not superior or inferior to anyone on this planet. We are all the same. With that approach, nothing is scary and everyone is valuable.

Voluntourism is said to be the fastest growing segment of the travel industry (itself one of the world’s fastest growing industries). Do you think this kind of travel can help the uninitiated understand the problems our planet is facing?

A lot people, myself included, scoff at the term “voluntourism.” We find it disturbing to think that privileged people are paying very large sums of money to spend a few weeks or months in a low-income country, somewhere in the global south or South/East Asia — to do what, exactly? How much of this money is being invested into the communities in which the voluntourists are traveling/visiting, and how much is supporting the Western-based organization? I think we know the answer.

On the other hand, I realize that this industry provides an organized, safe, and coordinated way for people who wouldn’t otherwise have the opportunity to visit certain parts of the world. I just don’t think the voluntourists should be misled. It is both their — and the organization’s — responsibility to fully understand the implications of their visit, and the impact of their visit on the community.

It’s difficult to measure how much this type of exposure can change one’s attitude toward and knowledge about a particular place and its inhabitants. I would advise anyone who has never left a highly-industrialized country and has enough resources, simply to board a flight to a poor developing country. The real learning and growing happens when you leave the comfort of a temporary expat community, the organized lodging, the capital cities and urban areas — and actually travel, by local means, to very remote and rural villages. It is these very raw, uncomfortable, and painful experiences — when people break the tourist habit of simply arriving, observing, interacting, taking, and leaving — that can lead to major epiphanies.

Readers — yay or nay for letting Vilma Ilic into The Displaced Nation? Tell us your reasons. (Note: It’s fine to vote “nay” as long as you couch your reasoning in terms we all — including Vilma — find amusing.)

img: Vilma Ilic and a friend from Zagreb nervously — owing to their leftover Catholic guilt — navigate the Virgin Mary’s blessed cove in the bluffs of Šibenik, a town on Croatia’s Dalmatian Coast (summer 2009).

STAY TUNED for what may or may not be tomorrow’s installment from our displaced fictional heroine, Libby, who has been in a state ever since her creator, Kate Allison, went missing on Halloween. Has she done an Agatha Christie on her? (What, not keeping up with Libby? Read the first three episodes of her expat adventures.)

If you enjoyed this post, we invite you to register for The Displaced Dispatch, a round up of weekly posts from The Displaced Nation. Includes seasonal recipes and book giveaways. Register for The Displaced Dispatch by clicking here!

Related posts: