When we announced this month’s theme — road trips — some of you may have wondered if we’d gone around the bend. Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance — really? That’s a book for roadgeeks or — if you get into its philosophical meanderings — Roads Scholars, not for Displaced Nation types, most of whom equate travel with boarding an international flight.

When we announced this month’s theme — road trips — some of you may have wondered if we’d gone around the bend. Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance — really? That’s a book for roadgeeks or — if you get into its philosophical meanderings — Roads Scholars, not for Displaced Nation types, most of whom equate travel with boarding an international flight.

Besides, road trips are for the young and restless — something you do when you’ve just graduated college.

But before you put the brakes on the road-trip idea again, let me convince you to take one more test drive. Only this time, instead of riding pillion on Robert Persig’s motorcycle, you’ll be seated in John Steinbeck’s camper station wagon next to his pet dog, Charley, on a 10,000-mile journey across America — from Long Island to Maine to Chicago to Seattle to California to Texas to New Orleans and back to New York City.

As the Nobel prize-winning writer puts his engine in gear, may I invite you to peruse our specially compiled John Steinbeck Encyclopedia of Road Trips.

A is for Autumn

John Steinbeck made a road trip across America in the autumn season and in the autumn of his life. He set out from his home in Sag Harbor, Long Island, shortly after Labor Day in 1960. He was 58 years old and not in the best of health. As Edward Weeks wrote of Steinbeck’s expedition in The Atlantic:

He set out with some misgiving, not sure his health would stand up to the 10,000-mile journey he envisioned; as he traveled, the years sloughed off him…

B is for Bestseller

Steinbeck wrote a book about his journey, Travels with Charley. It reached #1 on the New York Times bestseller list for non-fiction on October 21, 1962. To this day, the book retains a special place in the American imagination, despite attempts to challenge its categorization as “non-fiction” (see F).

C is for Charley

Meet Charley, Steinbeck’s middle-aged French poodle, one of the most civilized and attractive dogs in literature. He’s the genuine article, a real French poodle, having been born on the outskirts of Paris, where he also received his training. As his proud owner once said:

…while he knows a little Poodle-English, he responds quickly only to commands in French. Otherwise he has to translate, and that slows him down.

D is for Dog

For Steinbeck, a dog is an ideal companion on the open road as well as being an effective ice breaker:

A dog is a bond between strangers. Many conversations en route began with “What degree of dog is that?”

E is for Environment

Steinbeck was extremely attuned to the intimate connection between people’s lives and the rhythms of nature — weather, geography, the cycles of the seasons. But while nature animates his picaresque tale of his travels with his dog, one of his key observations was the the high price Americans would eventually pay for lives filled with ease and convenience. He felt they were trashing their environment for the sake of material prosperity. (A tad prescient, might we say?)

F is for Fictions

Journalist Bill Steigerwald set out to retrace Steinbeck’s steps on the 50th anniversary of his road trip. He concluded that not only had the Nobel laureate invented characters, he’d also embellished the hardships of his cross-country journey with Charley. In other words, this brilliant author’s much-loved book is loaded with creative fictions. (Wait, I thought all travel writers used some creative license — is there anything wrong with a novelist-turned-travel-writer using some?)

G is for Giant Redwoods

After sorting out his flat tire in Oregon (see O), Steinbeck visited the giant redwoods and ancient Sequoias and found them as awe inspiring as ever:

The vainest, most slap-happy and irreverent of men, in the presence of redwoods, goes under a spell of wonder and respect.

Steinbeck was further impressed when his dog, Charley, refused to urinate on the trees…

H is for Hurricane

The best-laid schemes of mice and men go oft awry, and Steinbeck had to delay the start of his trip slightly due to Hurricane Donna, which made a direct hit on Long Island. (Still, it could have been worse. It could have been Hurricane Irene!)

I is for International

While he never became an expat, Steinbeck moved to New York City and took quite a few international trips, mostly to Europe. He hoped that his road trip would enable him to reconnect with both the people and the landscape of his native land. He also wanted to see his birthplace — Salinas, California — one last time.

J is for Jamming

Steinbeck’s journey concluded with jamming Rocinante (see R) across a busy New York City street, during a failed attempt at making a U-turn. He reports having said to the traffic policeman:

Officer, I’ve driven this thing all over the country — mountains, plains, deserts. And now I’m back in my own town, where I live — and I’m lost.

K is for Knight-errant

A mainstay of medieval romance literature, the knight-errant wanders the land in search of adventures to prove himself a worthy warrior. Don Quixote is a famous example (see Q). Likewise, Steinbeck hoped to recapture his youth, the spirit of a knight-errant, through his travels. (Makes sense if you’re middle aged and your health is rapidly deteriorating — see P.)

L is for Language (of Road Signs)

Steinbeck closely observes the language of road signs during his trip across country. In New York State, he notes that the road signs are commands: “Stop! No turning!” But in Ohio, the language is gentler, with friendly advice rather than curt demands.

M is for Maine

Steinbeck reports that he learned not to ask for directions in Maine because locals don’t like tourists and tend to give them the wrong directions — another example of regional differences (see L).

N is for North Dakota

Upon arriving at Fargo, North Dakota, Steinbeck declares that the mentality of the American nation has grown “bland.” He fell head over heels in love with Montana, however. NOTE: Steinbeck’s account of meeting an itinerant Shakespearean actor outside the town of Alice, North Dakota, is disputed by the journalist Bill Steigerwald (see F).

O is for Oregon

Having his first flat tire on a remote back road in Oregon inspired Steinbeck to write a send-up of similarly desperate scenes in his most famous novel, The Grapes of Wrath:

It was obvious that the other tire might go at any minute, and it was Sunday and it was raining and it was Oregon.

P is for Poignancy

When Steinbeck set out on his road trip, he knew he could have died at any point along the way because of his heart condition. This knowledge suffuses Travels with Charley with a certain poignancy, and perhaps explains why it’s such a beloved book.

Q is for Quixote

As one might expect of a man who won a Nobel Prize in Literature, Steinbeck had a literary hero in mind when he set out on his road trip: Don Quixote. Like the ingenious gentleman of La Mancha, it seems that Steinbeck fancied himself a knight-errant in search of adventure (see K). He even named his camper truck for Quixote‘s steed (see R).

R is for Rocinante

As the narrator of Don Quixote explains, its hero feels obliged to find the right name for his horse:

Four days were spent in thinking what name to give it, because (as he said to himself) it was not right that a horse belonging to a knight so famous, and one with such merits of his own, should be without some distinctive name…

At last, Don Quixote calls the skinny steed Rocinante. In a nod to this fictional knight-errant (see K), Steinbeck christened the vehicle for his journey — a green GMC truck, which he’d had custom-fitted with a camper — Rocinante. He even painted the name across the side of the truck in 16th-century Spanish script.

S is for Salinas

Steinbeck was born in Salinas, California. He wrote his first stories about the Salinas Valley and was determined to see his hometown one last time before he died. Visiting a bar from his youth, he lamented the loss of several regulars as well as quite a few of his childhood chums, wondering if perhaps Thomas Wolfe was right (see Y).

T is for Texas

Steinbeck remarked of Texas that it was the kind of state that “people either passionately love or passionately hate.” He went on:

Texas is a state of mind. Texas is an obsession. Above all, Texas is a nation in every sense of the word. … A Texan outside of Texas is a foreigner.

Texas was also where Charley (see C) became ill for a few days and stayed in a veterinary hospital. NOTE: From Texas onwards, Steinbeck’s travel writing gives way to social commentary, culminating in the account of a school integration crisis he witnesses firsthand in New Orleans.

U is for U.S. Route 66

In mid-November of 1960, Steinbeck crossed the Mojave Desert and picked up the historical U.S. Route 66 at Barstow, California. He and Charley then drove 1,300 miles to arrive in time for a Texas-style Thanksgiving on a cattle ranch near Amarillo. U.S. Route 66, known colloquially as the “Main Street of America” or the “Mother Road” was a major path for those who migrated west. In Steinbeck’s classic novel The Grapes of Wrath, the poor family of sharecroppers, the Joads, make their way west from Oklahoma to California on U.S. Route 66.

V is for Viking Press

Travels with Charley was published by the Viking Press in mid-summer of 1962, several months before Steinbeck was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.

W is for Wanderlust

Steinbeck begins Travels with Charley by describing his wanderlust, saying he’s had a life-long impulse to travel and explore the world.

X is for Xena the Warrior Princess

This entry has nothing to do with John Steinbeck, but I have included it in case there are any women travelers who are having trouble identifying with the adventures of a rugged, broad-shouldered, six-foot-tall writer, and his desire to be seen as a knight-errant (see K). Xena the Warrior Princess reminds me of the title of Debbie Anderson’s best-selling guide for women who travel the open road: Simple Rules for…The Road-Warrior Princess.

Y is for “You can’t go home again”

When Steinbeck reached his birthplace of Salinas, he discovered the truth of Thomas Wolfe’s words “You can’t go home again.” Saying good-bye to his hometown for the last time was a bittersweet experience:

I printed once more on my eyes, south, west, and north, and then we hurried away from the permanent and changeless past where my mother is always shooting a wildcat and my father is always burning his name with his love.

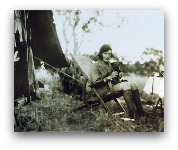

Z is for Zzzzz (under the stars)

Steinbeck reports that camping out with Charley in the American outback — where they enjoyed lots of zzzzz under the stars — was one of the highlights of their trip (though the veracity of that experience is now disputed — see F). But, despite the magnificent setting, both he and Charley often suffered moments of crushing loneliness. Ultimately, man and dog concurred that however much they relished their adventure, home is where the heart is.

So…are you inspired? Can you now see yourself motoring across country in the autumn and/or autumn of your life? And how about attempting a best-selling travelogue? (Or am I still driving you bonkers?!)

STAY TUNED for tomorrow’s post, a Displaced Q about none else than road trips(!).

If you enjoyed this post, we invite you to register for The Displaced Dispatch, a round up of weekly posts from The Displaced Nation. Includes seasonal recipes and book giveaways. Register for The Displaced Dispatch by clicking here!

Related posts:

Image: MorgueFile