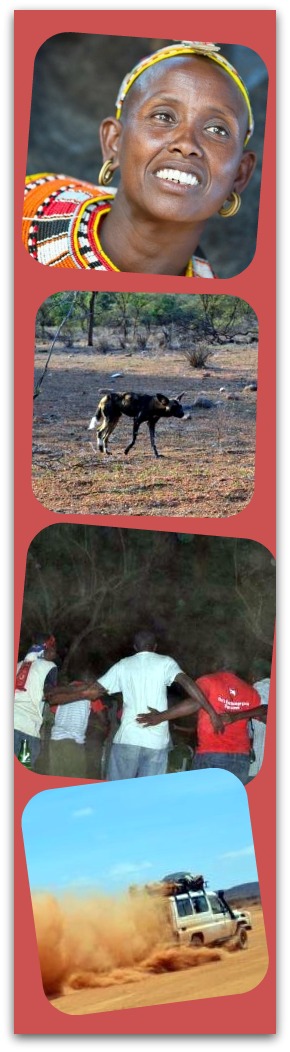

Today we are joined again by Kathleen Colson, who delivers the second part of her travel yarn on a trip she made to Kenya from September 8 to October 14. In Part 1, Colson shared some overall impressions of the country, which she has visited innumerable times — most recently in the role of founder and CEO of a micro-enterprise development organization known as the BOMA Project. Today she focuses on the portions of the journey having to do with that project.

Today we are joined again by Kathleen Colson, who delivers the second part of her travel yarn on a trip she made to Kenya from September 8 to October 14. In Part 1, Colson shared some overall impressions of the country, which she has visited innumerable times — most recently in the role of founder and CEO of a micro-enterprise development organization known as the BOMA Project. Today she focuses on the portions of the journey having to do with that project.

I founded The BOMA Project in 2005. “Boma” is a Swahili word for a livestock enclosure, but it also means “to fortify.” Our main program is the Rural Entrepreneur Access Project (REAP), which offers a seed-capital grant and business-skills training to small business groups of three people. The training is delivered by BOMA Village Mentors, who in turn are trained and supported by BOMA field staff.

So far, 2,688 adults, some of the poorest people on earth, are running 720 businesses, impacting the lives of over 14,000 children in northern Kenya.

As the project’s founder, I’ve had the great fortune to spend time with the pastoral nomads of this isolated region of Africa during several extended visits each year. In the first few years, there were four of us who traveled around the district meeting with village elders and groups of women. Since then, the organization has grown, and my trips have been busy hosting donors, photographers and consultants.

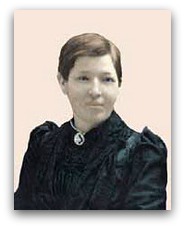

For this trip we would be back to the core team: Kura Omar, BOMA’s Operations Director; Semeji, our bodyguard; Omar, field support; and me, Mama Rungu. People always ask about my name, one that I have had for many years. It’s a long story, but a rungu is a warrior club. I got this name because someone thought I was tough.

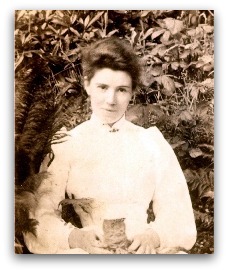

I looked forward to the long drives across the rough terrain of northern Kenya — talking with Kura non-stop, sometimes shouting above the corrugated roads. While we drive, Semeji sings and Omar spots for cheetahs and hoopoes, all the while listening for the sound of a bad tire. At night, stories are told under a brilliant night sky, and we listen to Semeji’s soulful warrior songs along with the hyena’s call.

Shiny is good

The BOMA Project now has 40 businesses in and around the village of Kargi and we are soon to launch 20 more.

Kargi, home to numerous clans of the Rendille people, has grown into a substantial village because it’s a road-accessible location where missionary and aid organizations can easily distribute food relief. (Periodic droughts are part of the life cycle of these arid lands.)

BOMA has worked hard to establish ourselves in this village — keeping in mind that we also had to keep our staff safe in an area that sees frequent ethnic conflicts over livestock. Now there is tremendous enthusiasm for our work, including from the village leadership. The chief has told Kura:

…these BOMA people, they look shiny.

Clean, healthy, shiny. Shiny is good.

The case of Ndebe Arbele

In the Rendille village of Falam, near Kargi, Kura insisted that I meet Ndebe Arbele, a member of one of the BOMA businesses. BOMA had given her business group, May Yeel, a seed capital grant of $150 and they used it to buy food, beads, washing powder and other small essentials in Marsabit, a town on Africa’s main artery, the Cape to Cairo Road — which they now sell to residents and travelers in their village.

Ndebe and her partners have attended BOMA business-skills training programs, and soon they will start a training program on savings. After just two short months they were able to distribute profits, and according to their record book, they now have savings and cash on hand of 5,300 shillings, or about $56.

As Kura translated, Ndebe told me about her son who was bitten by a rabid dog. The medical treatment was 4,000 shillings for four injections. She told me, “If it was not for this business, I would not have been able to pay for the medical treatment for my son. Many children here die from rabies, but not my son.”

I am very aware when I visit with our BOMA businesses, that I am sometimes told what I want to hear. On this occasion, I decided to push back.

“But didn’t you also receive money from HSNP [Hunger Safety Net Programme]? I am looking at your group’s record book and I don’t see how the 4,000 shillings came from the BOMA business,” I said to her.

Ndebe looked down. “Yes, you are right. I also took my HSNP money to pay for the shots.”

She looked up at me with tears in her eyes, then said:

Please don’t take this business away from me. All my life I have been a beggar. I used to be idle, waiting for food relief to feed my children. Now I am a trader. Now I work every day. From others we get relief, but it always ends. This business stays with us, and now I am someone. Please, please don’t take this away from me.

I suddenly realized that it is here that we stake our claim. We can provide grants and training so that women like Ndebe can earn an income that will help her care for her seven children. But the human spirit craves dignity and respect more than it seeks wealth, and that is what we had given Ndebe. It was enough.

“I could never take this business from you, Ndebe. It is yours forever. Thank you for telling me why this business is important to you. I will always come and visit you when I am here, and I want you always to tell me what you feel in your heart.”

“Kalath (thank you), Mama Rungu.”

A gloomier picture

In another Northern Kenyan village, Lengima, BOMA has facilitated the building of a school through the Dorothea Haus Ross Foundation. Currently, “school” is taught under a tree, with a blackboard and a volunteer teacher. For most of the students, there are no desks, no chairs, no paper, no pencils — not a single thing that would enrich the learning experience.

The whole village is involved in the building of the school. The men do the hard labor and each woman has been asked to collect a pile of stones — equivalent to a wheelbarrow-size load — for which they receive 50 shillings (55 cents).

The poverty in Lengima is extreme. Traditionally, the area relies on livestock as a source of income and food, but in times of drought, the men move the livestock elsewhere.

When we visited this time, a period of extreme drought, many of the children had the telltale signs of kwashiorkor (protein malnutrition), with reddish hints in their hair and extended bellies. The women were all painfully thin.

I met with Nalebicho Koitip, an older woman and a member of a BOMA business in the village, called Nkabe. She told me:

This drought has taken our livestock and our husbands. We keep our children alive with the small profits we make in this business. But it is hard because those without a business are turning to us for short-term food credit.

Locals must lead

In each village, we have BOMA Village Mentors. Using standard of living indicators — household assets and nutritional information — the Mentors select the “poorest of the poor” residents who are also enterprising and willing to work.

One of the highlights of my trip was attending BOMA’s Mentor University — our annual training session for the 26 BOMA Village Mentors — in South Horr.

This year, the goal of local leadership was a reality. I was now an observer. I said hello but was not expected to do anything else.

Sarah Ellis, one of our new researchers, has developed a micro-savings program for REAP participants, and at the meeting she introduced the new program to our Mentors. They will be the ones responsible for implementing the program region-wide. By regularly setting aside committed funds in a safe location, we believe we can provide insurance against the regular shocks that are typical for people who live in extreme poverty. It can also become a source of savings-led credit for BOMA grant recipients to grow their businesses.

Fresh ideas, goals

I always go to Kenya with lots of ideas and come back with even more. In the months prior to this trip to Kenya, I had spent time reading about the success of healthcare in Africa. While economic interventions, in general, have not been successful — incomes across the continent are down or stagnant — healthcare delivery has done reasonably well. The book Getting Better: Why Global Development Is Succeeding — And How We Can Improve the World Even More, by the economist Charles Kenny, is a fascinating read.

I wondered if we could apply some of the lessons learned by community healthcare workers in Africa to our team of BOMA Village Mentors.

In our last impact assessment, we had a 4 percent failure rate of the first 100 businesses. So I asked the BOMA team, “What if our businesses were patients? Would we tolerate a 4 percent failure rate?”

Once we started focusing on our failures, we became more imaginative, more creative. Every organization, for profit or not, likes to focus on its successes. If you are a nonprofit, you especially want to tout your successes, as this enables you to secure donations.

When we focused on our failures, however, we suddenly realized what we had to do — strengthen the training and support of our BOMA Mentors, the people at the heart of our program. We needed to give them the resources to fortify the success of BOMA businesses. We set a zero percent failure-rate goal for the following year.

Asked to say a few words at the end of the Mentor University meeting, I shared the concept of zero percent failure. It was a goal — a lofty goal — but I could sense the confidence in the room.

Our Mentors come from communities that have been overwhelmed by aid organizations that keep them on life support. Our program represents an opportunity to bring out the strength and resilience that resides in all of us.

Readers, any questions or comments for Kathleen Colson on her travel yarn or the BOMA Project?

For more details on Kathleen Colson’s recent East African journeys, go to the BOMA Project blog. Those familiar with the Matador Network may be curious to note that the BOMA Project was recently listed as one of the top 50 organizations “making a world of difference.”

STAY TUNED for Monday’s post on the “celebrity’s burden,” by Displaced Nation founding contributor Anthony Windram.

If you enjoyed this post, we invite you to subscribe to The Displaced Dispatch, a weekly round up of posts from The Displaced Nation, plus seasonal recipes, book giveaways and other extras. Sign up for The Displaced Dispatch by clicking here!

Related posts:

Images (top to bottom): A child in Lengima helping to collect stones for the building of the village school; a BOMA business in the village of Ngurunit; Kura Omar, BOMA’s man in Northern Kenya; a “taxi” full of BOMA Village Mentors, at the end of the three-day Mentor University training program.